Return to Standish families of the Manor of Duxbury.

Return to - Standish Family of the Burgh - part 1.

![]()

Standish Family of the Burgh - part 2.

The Stanley family the Lords of Lathom House Lancashire.

&

The Kings and Lords of Mann.

Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby.

.After the death of his father in

1459, Stanley inherited his father's titles, including that of King of Mann and

Baron Stanley. Stanley owned what is now Tatton Park in Cheshire. Stanley

remained in favour with successive kings throughout the Wars of the Roses until

his death in 1504. His marriage to Eleanor, sister of Richard Neville, Earl of

Warwick, did him no harm, even after Warwick was toppled from power, and he

took as his second wife Margaret Beaufort, whose son, Henry Tudor, was the

leading Lancastrian claimant to the throne.

King Richard III unwisely continued to trust Thomas Stanley and his brother, William, even after he had briefly imprisoned Thomas in 1483 on suspicion of conspiracy. At the Battle of Bosworth Field, the Stanleys deliberately hesitated before coming in on the side of the Lancastrians at a crucial moment, despite Richard holding Thomas's eldest son, Lord Strange, hostage for his father's continuing loyalty, and allegedly issuing the order for his execution. Following Richard's death, Thomas is supposedly to have retrieved Richard's lost crown from the battlefield and placed it on the head of his own stepson. In recognition, Henry created him Earl of Derby on October 27, 1485, and his fortunes continued to flourish. His brother, William, made the mistake of supporting the pretender Perkin Warbeck, and was executed for treason in 1495.

1399 – 1504. Kings of Mann.

- Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland (1399-1405)

- John I Stanley (1405-1414)

- John II Stanley (1414-1437)

- Thomas Stanley, 1st Baron Stanley (1437-1459)

- Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of Derby (1459-1504)

1504

– 2008. Lord of Mann

The son of Thomas Stanley, 2nd Earl

of Derby, did not take the style

'King', and he and his successors were generally known instead as Lord of Mann.

However, the Latin style Rex

Manniae et Insularum (King of Mann and the Isles) continued to be

occasionally used in official documents until at least the 17th century.

In 1765 the title was revested in the Crown

of the United Kingdom, thus today the title 'Lord of Mann' is used by Queen

Elizabeth II.

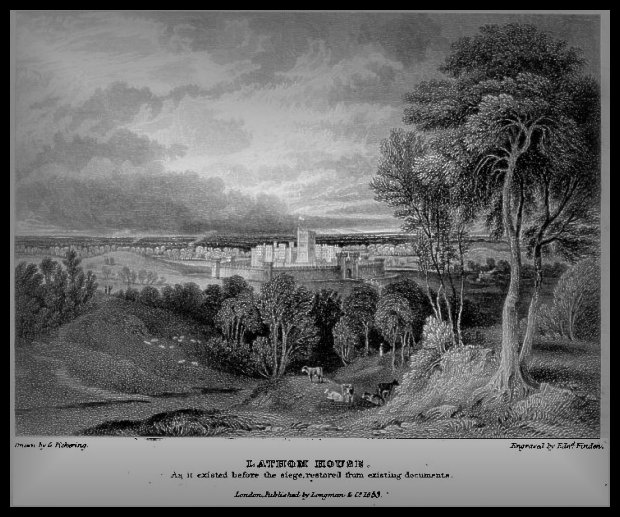

1644. The Siege of Lathom House.

Eleanor - Countess of Derby

A loyal Royalist,

James Stanley, 7th Earl of Derby, the lord at Lathom House was ordered by

Charles I to fortify the Isle of Man against a possible Scottish invasion, and

then on to the northern campaign. His wife, Charlotte de la Tremoüille was left

in charge of what turned out to be the last remaining Royalist stronghold in

Lancashire.

Thomas Fairfax saw

Stanley's absence as an opportunity to strengthen the Long Parliament's

position in Lancashire and set out to conquer Lathom House.

Thomas Fairfax.

Immediately after

the fall of Warrington, the Roundheads requested that the countess acknowledge

the parliament and surrender her house, but she refused on the grounds that

doing so would dishonour her husband. But she offered to limit herself to

defending her home, and this postponed further attacks on her position.

Artist's impression of Lathom House

A 6-foot thick wall defended the house with 9 towers (each with 6

cannon) and a strongly fortified gatehouse. A high tower (the 'Eagle Tower')

stood in the centre.

While the Earl was in the Isle of Man rounding

up an army to defend the island against a possible invasion by the Scots, his

wife the Countess of Derby (Charlotte de la Trémouille) built up a garrison of

300 men to defend the house and plentiful supplies.

Feb 28th 1644. Sir Thomas Fairfax arrives and summons the House to surrender.

The Countess requests a week to consider. Fairfax leaves the siege to his

cousin William Fairfax

Mar 12th 1644. The bombardment begins. The besieged make

effective sallies to attack the Roundheads whose artillery proves inept and

makes little effect on the walls.

Mar 24th 1644. William Fairfax then moves away and leaves

the siege to Colonel Rigby. Rigby sends a summons for surrender to the

Countess...who tells the messenger he should be hanged at the gate.. "Carry," said she, "this answer back to Rigby

(tearing the paper), and tell that insolent rebel, he shall have neither

persons, goods, nor house. When our strength and provisions are spent, we shall

find a fire more merciful than Rigby; and then, if the providence of God

prevent it not, my goods and house shall burn in his sight; and myself, children,

and soldiers, rather than fall into his hands will seal our religion and

loyalty in the same flames."

May 23rd 1644. A final summons was sent to the Duchess She replied,

"the mercies of the wicked are cruel," and that unless they treated

with her lord, "they should never take her, nor any of her friends

alive."

May 25th 1644. Prince Rupert

arrives to relieve the siege. Rigby flees to Bolton and the Countess retires to

the Isle of Man.

The heroic defence of Lathom House by the

Countess of Derby earned her a place in the heroines of history.

The house was eventually taken by the Roundhead General Egerton on

Dec 6th 1645 and was ruined.

![]()

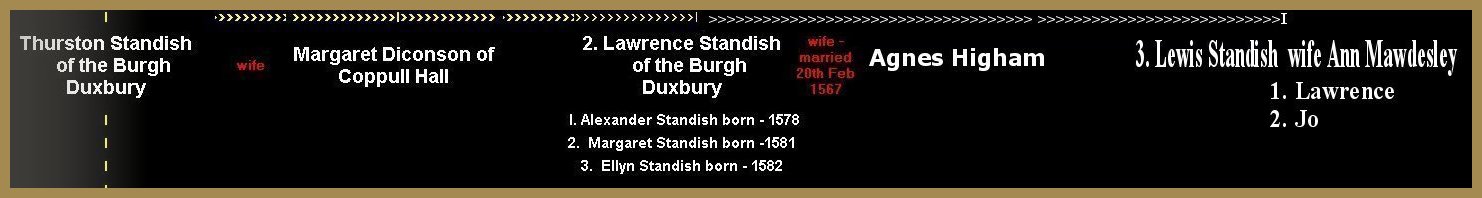

Lewis Standish of the Burgh, Duxbury Manor.

Soldier - Adventurer - Rogue - a man for all seasons - a son of the Standish Family of the Burgh.

Lewis was like Myles a one off Standish family christian name. Lewis Standish unlike his cousin Myles did leave a paper trail in the family documentation to record his illustrious deeds and also his knavish behaviour. Lewis started life well making an excellent marriage to Anne Mawdesley a daughter of the Mawdesley family of Mawdesley Hall. Myles Standish in his will of 1655 claimed land in Mawdesley and by coincidence the Mawdesley family were the owners of land or property in many of the locations named in the will of Myles.

Mawdesley Hall - Mawdesley - Lancashire.

In 1563 Lewis & Anne had a son Lawrence Standish - parish register of St. Laurence Chorley.

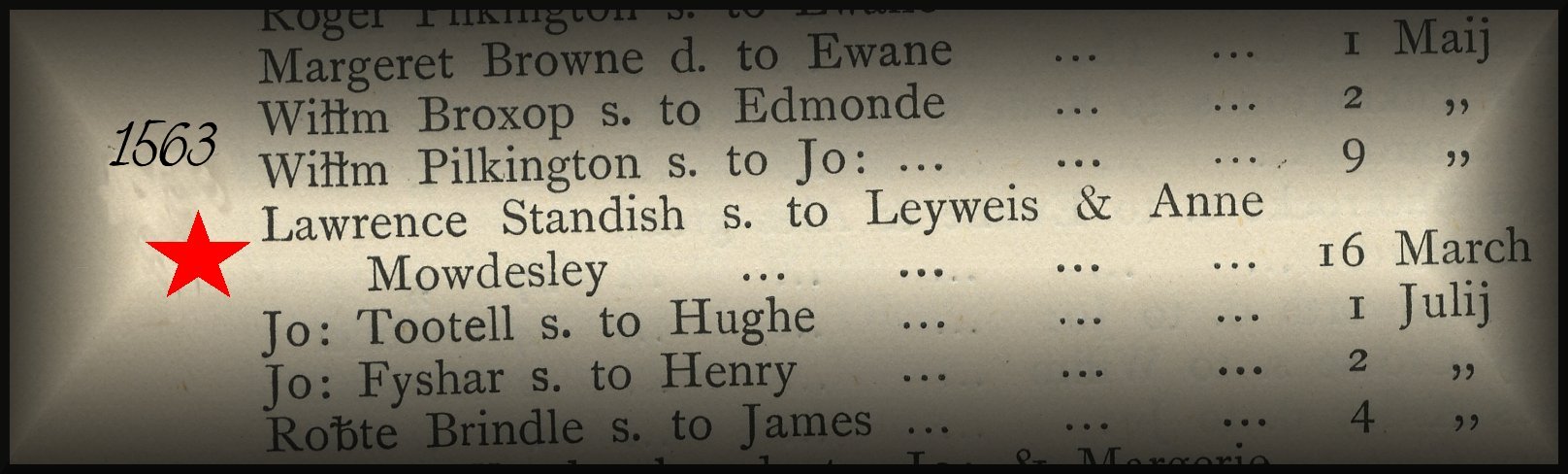

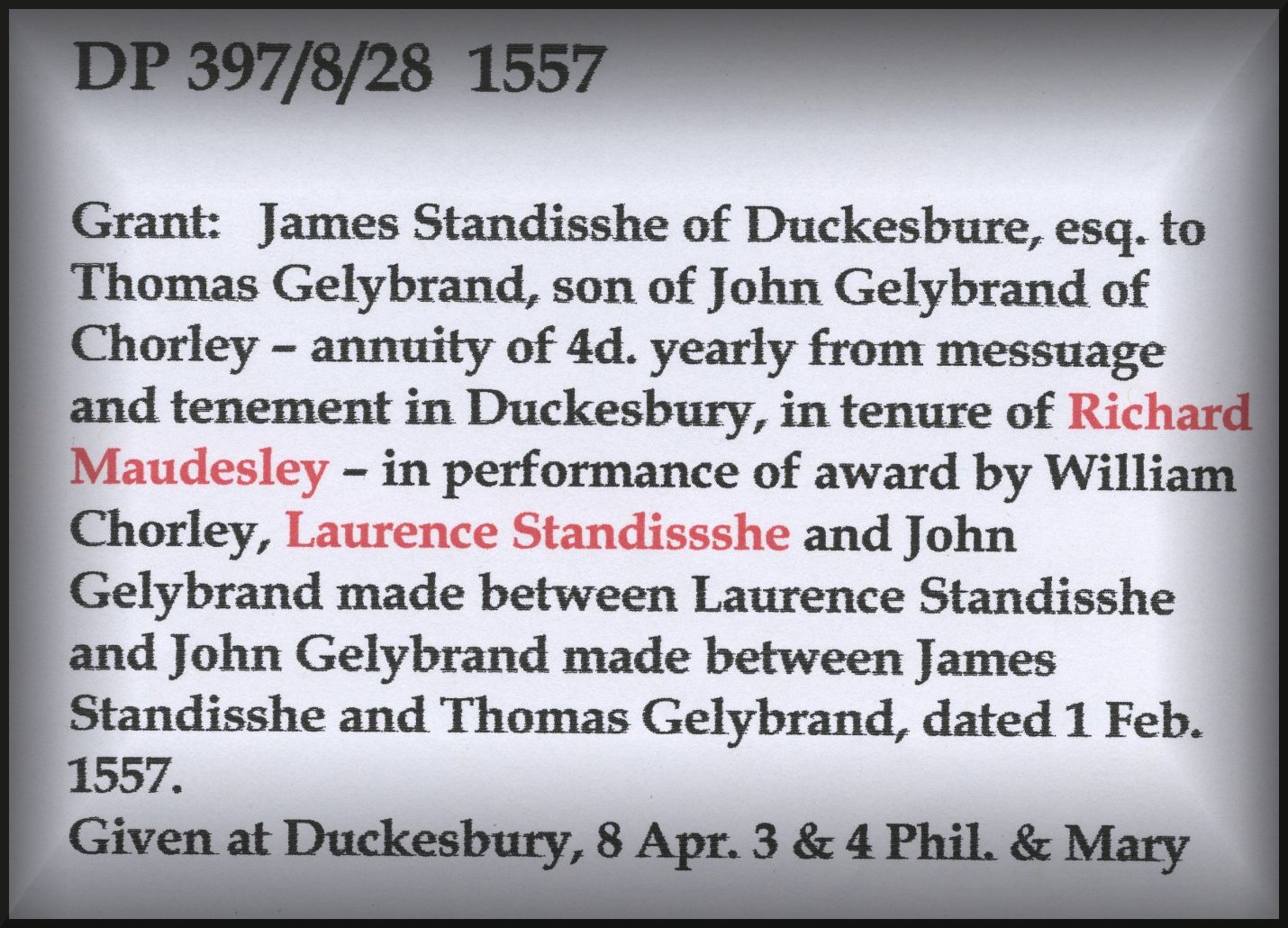

Date 1st February 1557. Land in Chorley and Duxbury - agreement between the Standish and Mawdesley families.

This document is signed by James Standish Lord of the Manor of Duxbury and Laurence Standish of the Burgh, Duxbury Manor then by Richard Mawdesley.

Original document - DP397/8/28 date 1st February 1557.

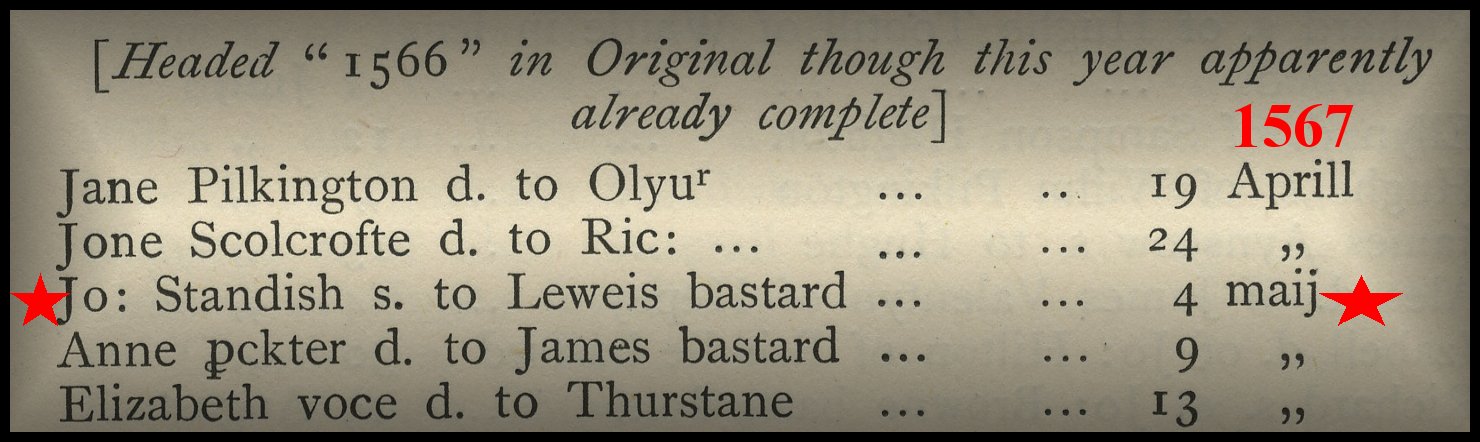

Date 4th May 1567. The register of the church of St, Laurence, Chorley, Lancashire.

Lewis Standish confessed to one of his many sins to spare a noble lady being named the mother of his illigitamate son Joseph in the parish register.

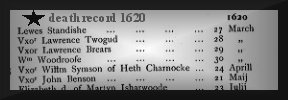

Date 17th March 1620. The register of the church of St, Laurence, Chorley, Lancashire.

The death record of the one and only - the inimitable Lewis Standish.

![]()

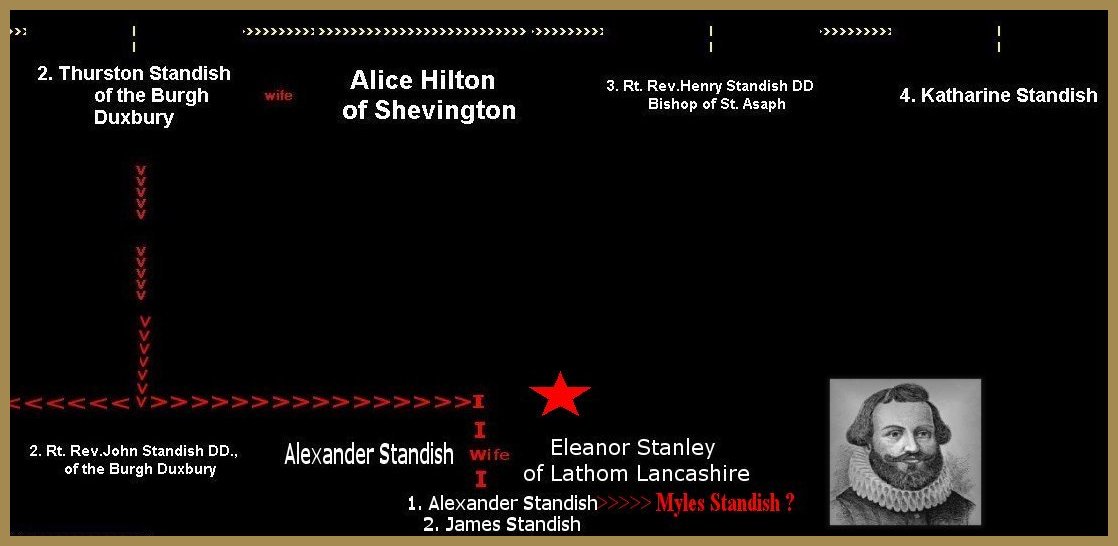

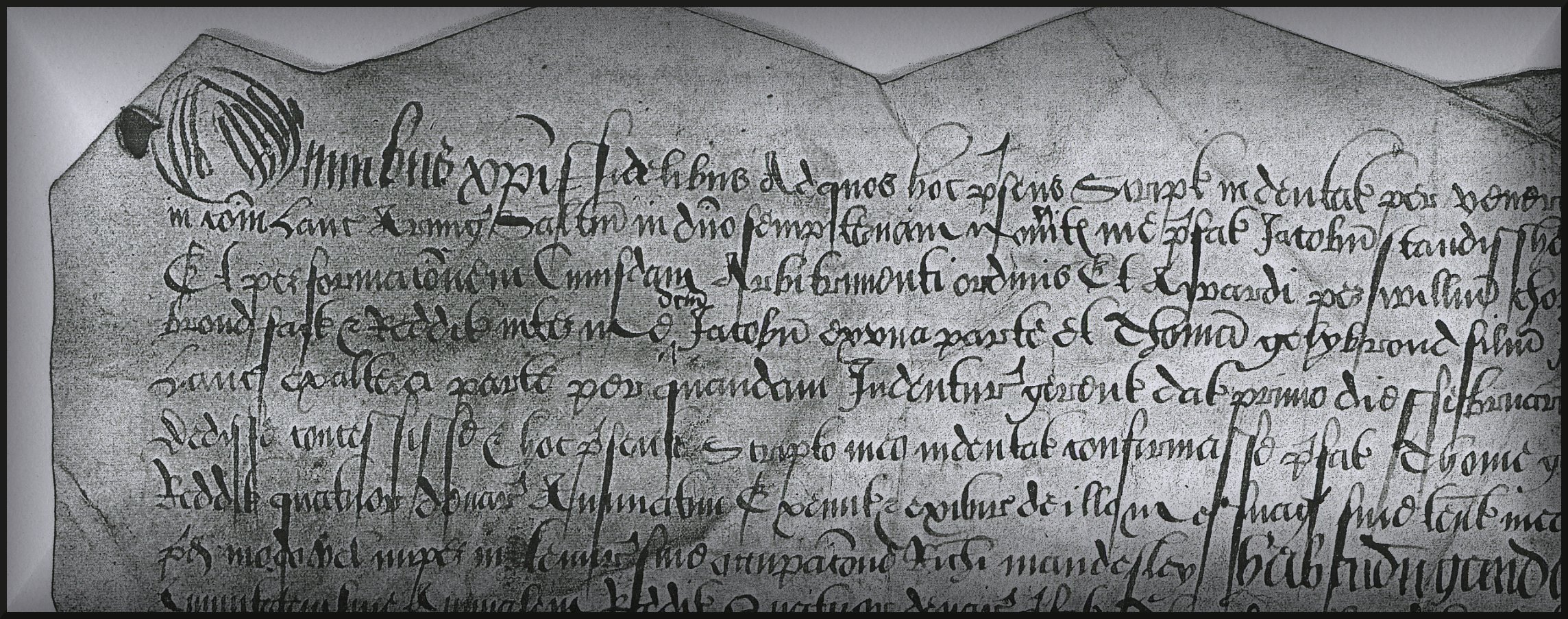

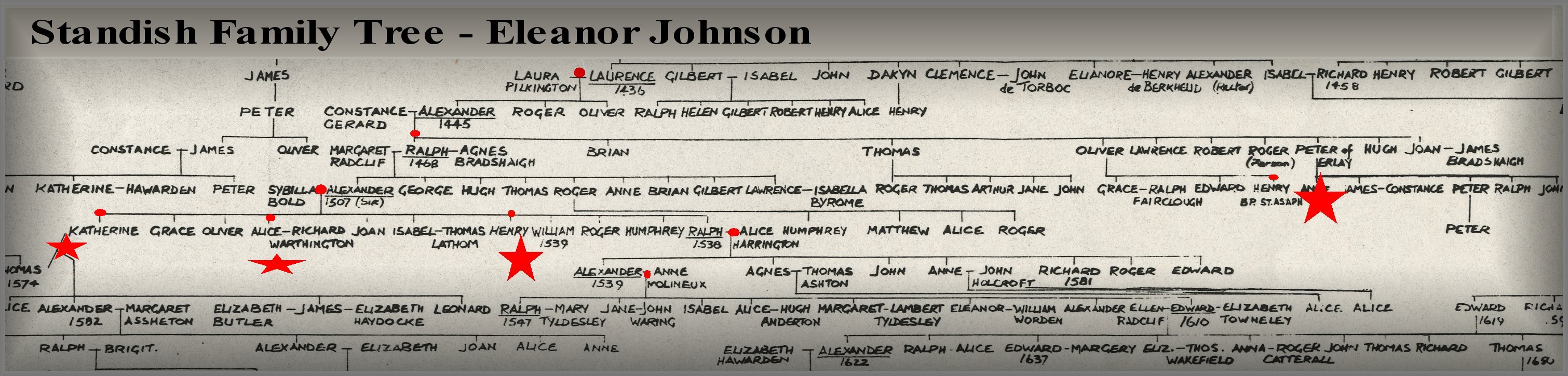

Three Key Son's

Henry- James - John sons of the Standish family provide a link between Standishes of the Burgh & Pele at Duxbury and Standish of the Manor of Standish.

1. Henry Standish, (c.1482–1535), Bishop of St Asaph - Uncle of John Standish, and James Standish.

2. James Standish, (c 1498-1566), Lord of the Manor of Duxbury 1515 - 1566 - nephew of Henry Standish, Bishop of St Asaph

3. John Standish, (c.1509–1570), Church of England clergyman - nephew of Henry Standish, Bishop of St Asaph

Katharine Standish (the mother of James Standish Lord of the Manor of Duxbury 1515 - 1566) was the daughter of Sir Alexander Standish (Lord of the Manor of Standish 1468 – 1507). Katharine Standish was also the sister of Thurston Standish of the Burgh upon Duxbury Manor and the sister of Henry Standish the Bishop of St. Asaph. Katharine Standish was the aunt of John Standish, (c.1509–1570), Church of England clergyman the son of Thurston Standish.

1. Henry Standish bishop of St Asaph.

Henry Standish, (c.1482–1535), bishop of St Asaph, was born at Standish, Lancashire,(according to Dugdale) a son of Alexander Standish. He was educated at the Franciscan school in Hereford, at Oxford, where he had proceeded DTh by 1502, and then at Cambridge. A Franciscan friar, he became warden of Greyfriars, London, about 1508, and later Franciscan provincial, before his consecration as Bishop of St Asaph. He was also rector of Standish, Lancashire (in commendam with his episcopal appointment). He preached before King Henry V111 in February 1511 and thereafter became a court favourite, asked back in the spring of every year from 1515 to 1520 (receiving 20s. each time). His sermons, much to Henry's liking, brought him an important place among the king's spiritual advisers.

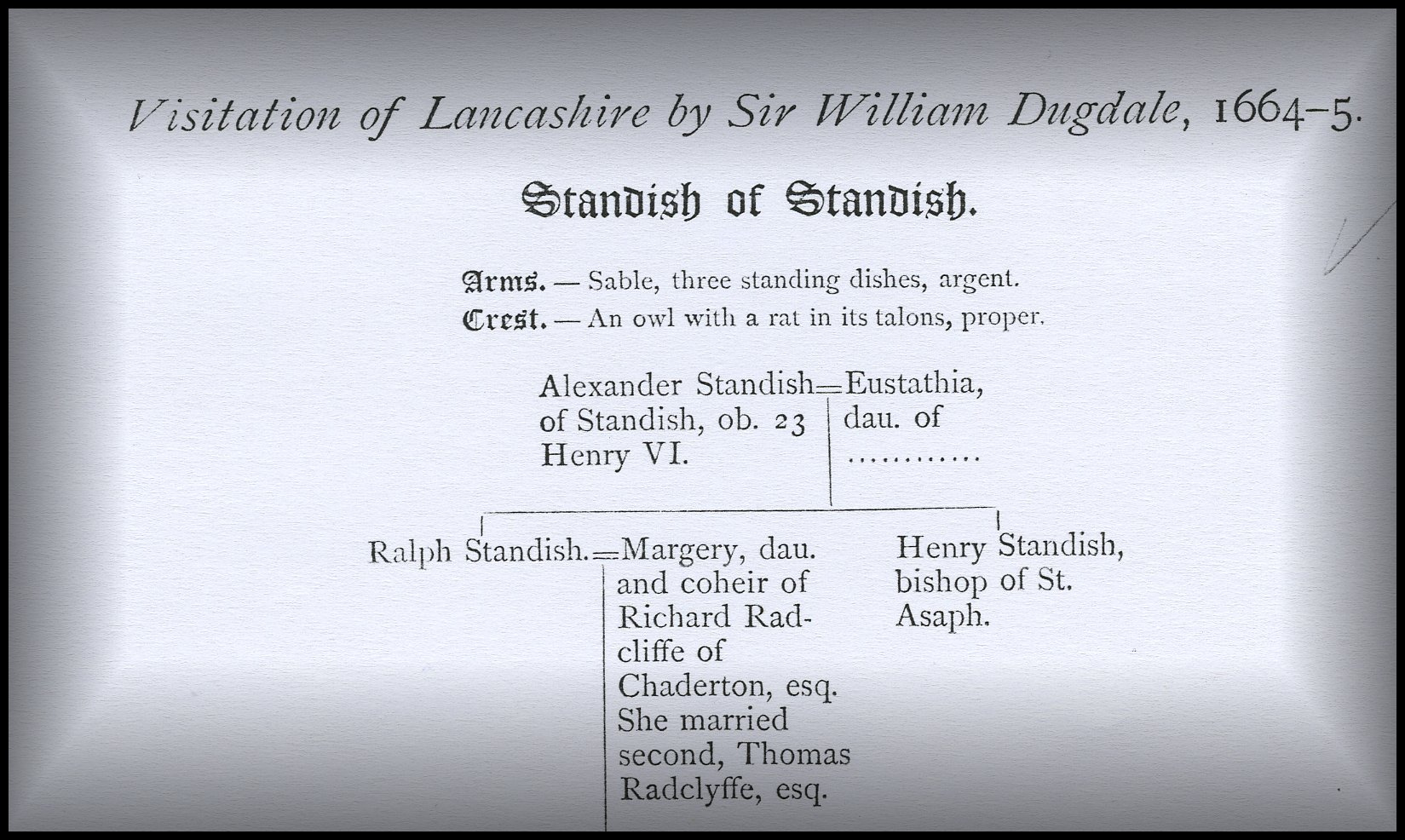

Henry Standish, Bishop of St Asaph has been located by researchers into the Standish family at different points in the family tree. Thus was Henry Standish (1482–1535) son of Alexander Standish Lord of the Manor of Standish 1468 to 1507 the Bishop of St Asaph? In the year 1664 Sir William Dugdale records Henry Standish, Bishop of St Asaph as the son of Alexander Standish Lord of the Manor of Standish 1434 - 1445 and brother of Ralph Standish born 1421, this dating would result in Henry Standish acting as Bishop of St Asaph at the great age of 100 years. Consequently many learned scholars have suggested that the visitation recorded in 1664 by Sir William Dugdale was incorrect and the correct record is "Henry Standish, Bishop of St Asaph, the son of Alexander Standish Lord of the Manor of Standish 1468 - 1507 and brother of Ralph Standish born 1479".

![]()

2. James Standish - Legal Dispute date 1534.

1534. James Standish Lord of the Manor of Duxbury versus Henry, Bishop of St. Asaph.

James Standish versus Henry, Bishop of St. Asaph, as Arbitrator between Abbot of Whalley and James Standish re Title to Tythes of Standish Parsonage, &c. the Right Honourable Sir William Fitzwylliam, Knight.

James Standyshe [Standish] of Dukkesbury [Duxbury] in the county of Lancaster, Esq., complains that whereas divers variances and strifes were heretofore depending between the Abbot and Convent of the Monastery of Whalley of the one part and plaintiff on the other part, for the appeasing whereof Henry now Bishop of St. Asaph and parson of Standyshe [Standish] desired plaintiff to submit all the said variances to his judgment, promising that if he would so do he should occupy all his tithe of Dukkesbury [Duxbury], parcel of his parsonage of Standyshe during all the time that he was parson there, he (plaintiff) paying yearly to the said Bishop for the same 5 marks. Thereupon obligations with conditions were made between plaintiff and the said Abbot to abide by the award and judgment of the said Bishop: which obligations plaintiff has kept although the award made by the said Bishop was to his great loss and hindrance and to his disherison. Plaintiff occupied the said tithe for 2 years and paid his rent for the same, but now the Bishop has taken it away from him although he has spent a great deal on the parish in many ways, and has also brought divers actions for trespass against plaintiff for occupying the same.

Prays that the said Bishop may be compelled to answer the premisses.

S. 1. a. The answer of Henry, Bishop of St. Asaph.

It is true that he was chosen to arbitrate between the plaintiff and the said Abbot by the friends and "lovers" of plaintiff, and that the said parties then bound themselves in the sum of £100 to abide his award. The said Bishop never promised plaintiff the tithe of the hamlet of Dukysbury [Duxbury] and plaintiff never suffered any loss through him. The said Bishop took a great part of the said tithes at the time of the "compromitting" and has ever since converted them to his own use, as in threshing of corn and grain for his household at the parsonage of Standishe, and other good works of charity, such as making of ways and giving of alms to poor people in the said parish, and not for his own covetous mind as plaintiff alleges, for it is bestowed in building and repairing the said parsonage which was in extreme ruin, and in hospitality. Plaintiff has several times unlawfully taken and carried away part of the said tithes after the 10th part thereof has been severed from the 9 parts, and has interrupted deponent's servants while gathering the same, by reason whereof witness has commenced an action for trespass against him at Lancaster. Plaintiff has done nothing in the said parish beyond marling his own demesne lands, to his own singular profit and commodity, and to do this he has borrowed money of deponent.

S. 1. b. ***The replication of James Standysshe. "Plaintiff is very nere kynnysman to the said Bysshopp."

S. 1. c. "The rejoinder of Harry, Bisshop of Seynt Asse." [Asaph]. Says that plaintiff was right well contented and pleased in every way with his award.

S. 1. d. Commission dated 04 Jul [1534] , 26 Henry 8., directed to Sir Henry Faryngton, Knight, Sir Roger Bradsha, Knight, Rauff Standyshe, Esq., and Roger Asshowe, Esq.

S. 1. e. Commission dated 17 Feb [1535] , 26 Henry 8., directed to Sir Hen. Faryngton, Knight, and Sir Thos. Southworth, Knight.

S. 1. f. Commission dated 28 Nov [1534] , 26 Henry 8., directed to above.

S. 1. g. Interrogatories on behalf of plaintiff.

1. Imprimis, whether the said Bishop knew of any variance between the parties?

2. Whether the Bishop required plaintiff to "compermyt" all the said matters to him and to make him arbitrator.

3. As to what ground, pasture and common, the variance was depending?

4. Whether the Bishop promised plaintiff that if he would make him arbitrator he should have the farm of the parsonage of Dukkesbury [Duxbury]?

5. Whether plaintiff made the Bishop arbitrator between himself and the Abbot?

6. Whether the Bishop ever made any award between the parties?

7. Whether the award was in writing under the seal of the Bishop, and whether he set his hand thereto?

8. Whether the said James Standyshe, after the award, occupied the tithe of Dukkesbury [Duxbury]?

9. Whether Alexander Standyshe and John Wryghtynton at the command of the Bishop received any rent from plaintiff?

S. 1. h. The answer of the Bishop of St. Assaph [Asaph].

1. This the Bishop grants.

2. Does not remember whether he asked plaintiff or plaintiff him.

3. Does not know.

4. This he denies.

5. This he grants.

6, 7. If there were an award it is under the Bishop's hand and seal, and was delivered to the said James Standyshe.

8. He cannot tell.

9. The Bishop himself received nothing; whether others in his name had anything he cannot say.

S. 1. i. The Commissioners certify that on the 23 Mar last, they went to the parsonage of Standyshe, then the dwelling house of the said Bishop, he being there present, and showed him the said Commission. He refused to be sworn on the holy Evangelists, otherwise than he had done before, and said he would make his answer and send it with his own hand: which answer is hereto annexed.

S. 1. j. At Standysshe, 23 Mar.

S. 1. k. Copy of above.

On the 15 Jan [1535] last, We the said Commissioners went to the parsonage of Standyshe and desired the Bishop to be sworn on the holy Evangelists to the truth of his answer, but he said it "wose not mett for no lorde of the parliament ner other greate prelett to be sworne oder wisse then to lay ye hande on ye brest, how be itt, he said, he wold lay his handes on his brest and so saye his said answer was true." As his saying was contrary to our said Commission, we dare not charge him with his said oath. However, the Bishop then caused a new bill to be made which he signed with his own hands, we standing "aferrom" in the chamber from him, and then he laid his hand on his breast and said that all things in the bill were true: which bill he would have delivered to us desiring us to certify the same, but as all he did was on his own pleasure and contrary to our commission we refused to receive it or to meddle any further in the matter until we knew your further pleasure. Howbeit, we moved him to an agreement, but he said if he did agree he should lose his best friends "such as he loveth ye litill fynger better then he did all the body of James Standissh."

At Farrington, 20 Jan [1535]. 26 Henry 8.

S. 1. l. Memorandum, that on the 24 Oct , 26 Henry 8., the said Commissioners met at Standishe, and took the depositions following:

On the part of the said James.

Peres Caterall, servant to the said James, aged 24, says that he was present at Assheton in Makerfeld when the said James desired my lord of St. "Asshes" [Asaph] to be good to him, and to let him have the tithe as he had before. The said Bishop answered that he should have it, and a better thing too if he would be ordered by him.

Henry Garstan, tenant to the said James, aged 60, was with his master at the "grey freres," in West Chester, and there saw him walking with the said Bishop. Immediately after they had taken leave of each other, the said James showed deponent 5 marks or thereabouts which the said Bishop had lent him, with the promise of the said tithe or something better, but he was to keep it privy from the rest of the parish of Standish.

Richard Catterall, tenant to Nicholas Boteler, Esq., aged 54, was present at the parsonage of Standishe when the said Bishop promised plaintiff the tithe.

William Wigan, tenant to Elen Brown, aged 40, says that he formerly lived with plaintiff, who told him of the promise made by the Bishop. Lambe, servant of William Standishe, told plaintiff that the Abbot of Whalley would not abide by the award of the Bishop, but would rather forfeit his obligation.

Roger Plesyngton, servant to Rauf Arrosmyth, aged 40, knows that the said James has occupied the said tithe for 2 years. Edmund Lawe, tenant to Roger Asshawe, aged 40, says that during the 2 years the said James occupied the said tithe, he (deponent) carried away half the tithe for his hire, and James took the other half thereof. Robert Hyll, tenant to the said James, aged 46, as above.

The said Henry Garstan does not know the value of the loss of the said James, because before the award of the Bishop there was an award made between the Abbot of Whalley and Sir Richard Hoghton, Knight, for certain enclosures of 200 acres, wherewith the plaintiff was not content, but always claimed the 3rd part thereof and pulled down the ditches and cut down the woods upon the enclosures. Since the award made by the Bishop the said James has never had any advantage thereof.

NOTE.

S. 1. b. ***The replication of James Standysshe. "Plaintiff is very nere kynnysman to the said Bysshopp." -Katharine Standish mother of James Standish Lord of the Manor of Duxbury was the sister of Henry, Bishop of St. Asaph and she was also the aunt of John Standish,Church of England clergyman.

![]()

3. John Standish, 1509–1570 son of Thurston Standish of the Burgh Duxbury Lancashire.

John Standish, (c.1509–1570),

Church of England clergyman,belonged to the family of

Standish of Burgh, Lancashire, and was the nephew of Henry

Standish, Bishop of St Asaph. Admitted a scholar of Brasenose

College, Oxford, in 1524 he graduated BA on 16 May 1528. On 16 June following,

aged nineteen, he was appointed a scholar of Corpus Christi College, Oxford,

becoming a fellow in 1530. He proceeded MA on 17 July 1531 and relinquished his

fellowship. He was ordained priest at Lichfield on 24 February 1532 but

thereafter gravitated to London. By 1538 he had become praelector in theology

at Whittington College, also serving as a university preacher at Oxford that

year. After Robert Barnes had been burnt for heresy in 1540, defending his

protestant views at the stake, Standish published A Lytle

Treatise Against the Protestation of R Barnes at the Time of his Death,

which was answered by Miles Coverdale. Perhaps as a result of this literary

effort Standish was admitted BTh at Oxford in 1540 or 1541 and incorporated DTh

on 16 July 1542. On 3 December 1543 he was collated rector of St Andrew

Undershaft in London and on 30 June 1544 vicar of Northall, Middlesex, at the

hands of Edmund Bonner, bishop of London.

During the next five years Standish rapidly transferred his allegiance to the

evangelical camp and accordingly prospered under Edward VI. He was appointed

chaplain to the king in 1550 and on 12 July that year was presented by the

crown to the eighth prebend in Worcester Cathedral, receiving licence in 1552

to retain it though non-resident. In March 1551, probably as a result of the

government's drive at this time to promote protestant preaching in the north,

he was presented to the rectory of Wigan, Lancashire, although it must be

doubted that he was ever admitted. On 10 January 1553 he was instituted by

Nicholas Ridley, first protestant bishop of London, to the archdeaconry of

Colchester on the presentation of Sir Edward Norton. Later that year he was

admitted rector of Medbourne, Leicestershire.

Standish Deeds in a private collection - Lancashire England.

1. Bond date 1556 – Christopher Standish to John Standish son of Thurston Standish.

[May all men know, by these presents, that I, Christopher Standish, the son of James Standish of Duxbury in the County of Lancaster, esquire, am held and firmly bounden unto John Standish,

In the sum of twenty pounds of good and lawful money of England, to be paid to the same John, or his certain attorney, his executors or administrators, on the Feast of the Birth of our Lord next coming after the date of these presents.

To which payment, indeed, well and faithfully to be made, I do, by these presents, sealed with my seal, firmly bind myself, my heirs, executors and administrators.

Dated the third day of December in the third and fourth years of the reigns of Philip and Mary, by the grace of God, [King and Queen] of England, France and both Sicilies, Jerusalem and Ireland, defenders of the faith, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Milan, Burgundy and Brabant, Counts of Hapsburg, Flanders and Tyrol.]

![]()

Eleanor Johnson a very creditable Standish family researcher indicates the possibility that Henry Standish, Bishop of St Asaph could be the grandson of Alexander Standish Lord of the Manor of Standish 1434 - 1445 and not the son of the Alexander stated by Sir William Dugdale.

Eleanor Johnson also noted that Henry Standish born 1482 was a son of Alexander Standish Lord of the Manor of Standish 1468 to 1507 and that the said Alexander had a large family of ten or eleven children. Not all the children are positively documented.

One of his daughters Katherine, married Thomas Standish Lord of the Manor of Duxbury 1495 –1516 thus reuniting the two branches of the Standish family. Katherine would therefore have been the sister of Thurston Standish of the Burgh and Henry Standish, Bishop of St Asaph. Other daughters of Alexander (1)Joan, married James, son of William Bradshaigh of Haigh (2) Alice married Richard Worthington and (3) Isabel married Thomas Lathom.

The son and heir of Alexander Standish - Ralph married Alice, daughter and co-heir of Sir James Harrington of Wolfage in Northamptonshire. This marriage in 1497 brought in the manor of Brixworth into the Standish estates.

![]()

John Wilson.

The Eminent local historian John Wilson also addressed the question of the father of Henry Standish Bishop of St. Asaph quotes the visitation of Dugdale and the contrasting evidence of Gregson in his book Verses and Notes dated 1903. Gregson stated that Henry Standish Bishop of St. Asaph had a sister Agnes married into the Worthington family. None of the Henry Standishes cited as the Bishop of St. Asaph had a sister Agnes, however two of the Henry Standishes had a sister named Alice and only one of these sisters married into the Worthington family. In the family tree produced by Eleanor Johnson (above) the marriage of Alice Standish daughter of Sir Alexander Standish Lord of the Manor of Standish 1465 – 1507 to Richard Worthington is recorded in common with the family papers. Thus another indicator that Henry Standish Bishop of St. Asaph was the son of Sir Alexander Standish Lord of the Manor of Standish 1465 – 1507.

John Wilson - Verses and Notes dated 1903